Biophysical Characterization of Enveloped VLPs Using a Waters GTxResolve™ 2000 Å SEC Column, MaxPeak™ Premier 3 µm

Lavelay Kizekai, Balasubrahmanyam Addepalli, Sophia Kenrick, Matthew A. Lauber

Waters Corporation, United States

Published on December 19, 2025

Abstract

Enveloped virus-like particles (eVLPs) can be engineered to encapsulate viral capsids that can carry nucleic acids (DNA/RNA), proteins, or small drugs for gene therapy treatments and prophylactic vaccination. Their structure, which mimics native viruses by displaying membrane-bound antigens, makes them excellent vehicles for therapeutic and diagnostic applications. A robust analytical approach for the biophysical characterization of eVLPs using size-exclusion chromatography coupled with multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALS) is presented in this application note. The separation was achieved using an optimized mobile phase and a GTxResolve 2000 Å SEC Column, 3 µm, constructed with an optimized packing material specially designed with bonded hydrophilic, bridged ethylene polyethylene oxide (BE-PEO) modified particles, and MaxPeak Premier high-performance surfaces (HPS) Column hardware. The eVLP radius determined by batch dynamic light scattering (DLS) ranged between 60 and 160 nm, which was within the particle pore size distribution of the GTxResolve 2000 Å SEC Column 3 µm packing material. This study highlights the importance of method optimization and the advantages of SEC-MALS as a platform technique for characterizing complex biotherapeutics and biomolecular complexes.

Benefits

- GTxResolve 2000 SEC Column, MaxPeak Premier 3 µm for high recovery eVLP separations

- SEC-MALS for accurate, high-resolution size distribution and particle concentration

- Batch DLS for rapid screening of eVLPs particle abundance and size distribution

Introduction

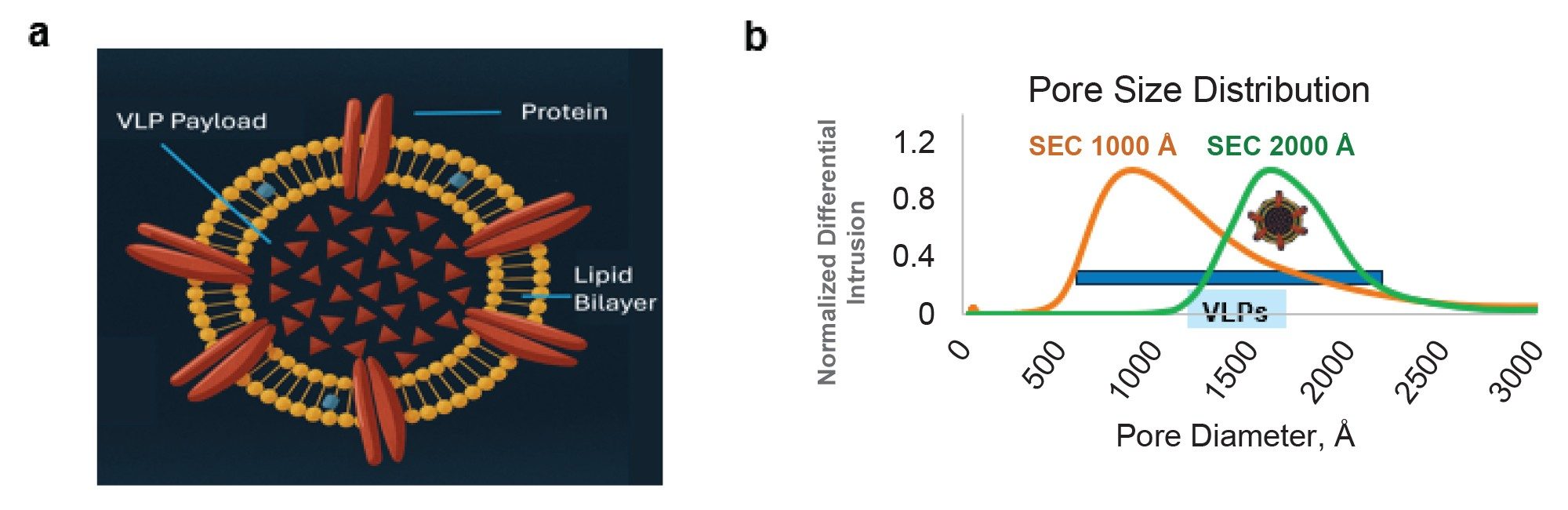

Virus-like particles (VLPs) are non-infectious nanostructures that mimic cell-infecting virions. VLPs are highly suitable for targeted drug delivery, immunization therapy, and diagnostics. Their suitability as biotherapeutics stems from their ability to protect nucleic acids or drug cargo from non-specific binding or degradation. Major advantages of VLPs include safety for immune-compromised individuals (tolerability), efficacy, high stability, and a reduced risk of mutations (due to the absence of genetic material) compared to traditional vaccines.1–2 Furthermore, they can be manufactured or modified chemically or genetically engineered for higher stability, uniformity, and functionality, making them viable drug delivery vehicles. VLPs are diverse and exhibit structural complexity. eVLPs contain host cell membranes called an envelope around the viral capsid, in contrast to non-enveloped VLPs (Figure 1a). The eVLPs closely resemble actual viruses in structure, presenting membrane-associated antigens that improve immunogenicity through surface glycoproteins or incorporation of engineered peptides or targeting ligands, making them highly customizable for therapeutic and diagnostic applications.3 eVLPs have been used to develop vaccines against viral diseases, including hantaan virus, hepatitis C virus (HCV), influenza A, and retroviruses.4 Out of the various requirements of a successful VLP candidate, characterization of structure, including lipid bilayer, glycoproteins, stability, integrity, and batch-to-batch consistency, remains the highest priority for deployment.5

SEC is a widely adopted method for integrity analysis of biotherapeutics. Molecular separation occurs based on the hydrodynamic size and the analyte’s access to the pores of the packed bed. SEC can resolve aggregates and fragments from the main drug product using a packing material with the right pore size. Besides the pore size of the packing material and particle chemistry, column technology plays a critical role in influencing the chromatographic peak shape and analyte recovery during the separation process. Waters GTxResolve 2000 Å SEC Column, MaxPeak Premier 3 µm minimize nonideal secondary interactions through specially designed and bonded hydrophilic, bridged ethylene polyethylene oxide (BE-PEO) modified particles and MaxPeak HPS Technology containing column hardware. This latter feature incorporates an organosilica barrier between analytes and metal hardware to prevent nonspecific adsorption, ensure reproducible recoveries, and method robustness.6 Meanwhile, the bridged ethylene surface crosslinks of the packing material enhance its chemical resilience while ensuring low noise levels when a column is coupled to a light scattering detector. The 2000 Å pores provide a suitable fractionation range for many medium and large-sized modalities and complexes with a hydrodynamic radius of ~90 nm, in contrast to 50 nm for GTxResolve SEC 1000 Å pore size particles (Figure 1b). Such a large pore size is well-suited for VLP analysis as their radii range from 40-100 nm.7

This application note describes the analysis of enveloped VLPs using method-optimization steps involving size-exclusion chromatography coupled with multi-angle light scattering for in-depth characterization of size distribution.

Experimental

Sample is an enveloped VLP Protein Isotype Control (Acro Biosystems p/n: VLP-N5213: HEK293-derived enveloped capsid protein isotype VLP (estimated Rh 50-150 nm) supplied in PBS, pH7.4 with trehalose as protectant and injected as-is for SEC-MALS. For Batch DLS, the sample was diluted at a 1:1 ratio with the mobile phase, and 5 µL was added to the cuvette.

The mobile phase used for SEC separations consisted of phosphate buffer (1-100 mM), KCl (0-400 mM), and other additives, such as polysorbate 80 (PS80) (60 ppm) and sucrose (up to 25%). The ideal mobile phase is Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS), 20 mM phosphate, 276 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, pH 7.4 (2X DPBS), 0.006% PS80, and 25% sucrose (125 mM). All mobile phase solutions were filtered through a 0.1 µm membrane before use.

Bovine thyroglobulin (BTG) (Sigma-Aldrich, p/n: T1001- l00 mg) was prepared at a 5.0 mg/mL concentration and filtered to 0.1 µm for light scattering alignment, normalization, and band broadening.

DLS: The DynaPro™ NanoStar™ Instrument was used to measure the hydrodynamic radius and total particle concentration of unfractionated enveloped VLP.

LC Conditions

|

LC system: |

ACQUITY™ Arc™ Premier System with Quaternary Solvent Manager (QSM) and Flow Through Needle Sample Manager (SM-FTN) |

|

Vials: |

Max Recovery Vials and Caps (Waters p/n: 186000327C) and Waters 300 μL Polypropylene Screw Neck Vial (Waters p/n: 186004112) |

|

Columns: |

GTxResolve 2000 Å SEC Column, MaxPeak Premier 3µm, 4.6 x 150 mm (p/n: 176006047). GTxResolve 2000 Å SEC Column, MaxPeak Premier 3 µm, 7.8 x 150 mm (p/n: 186011348). |

|

Column temperature: |

40 °C |

|

Sample temperature: |

6 °C |

|

Sample manager washes: |

18.2 MΩ*cm water |

|

Seal wash: |

10 % HPLC grade Methanol / 90 % 18.2 MΩ water (v/v) |

|

Injection volume: |

80 µL |

|

Flow rate: |

0.30 mL/min |

|

Mobile phase A: |

20 mM phosphate, 276 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, pH 7.4 (2X DPBS), 0.006% PS80, and 25% sucrose (125 mM) |

|

Samples: |

Enveloped VLP (ACROBiosystems p/n: VLP-N5213: HEK293-derived enveloped capsid protein isotype VLP (estimated Rh 50-150 nm). |

|

Gradient: |

Isocratic |

|

LC system control: |

Empower™ Chromatography Data System (CDS) |

|

UV detection: |

ACQUITY 2489 TUV Detector |

|

UV wavelength: |

Channel 1: 280 nm and Channel 2: 220 nm |

|

Multi-angle light scattering (MALS): |

Wyatt Technology™ DAWN™ MALS Detector with a WyattQELS™ embedded online DLS Module |

|

Refractive index (dRI): |

Wyatt Optilab™ Differential Refractive Index (dRI) Detector |

|

Data acquisition and analysis: |

ASTRA™ 8.3 Software |

Results and Discussion

Mobile Phase Optimization

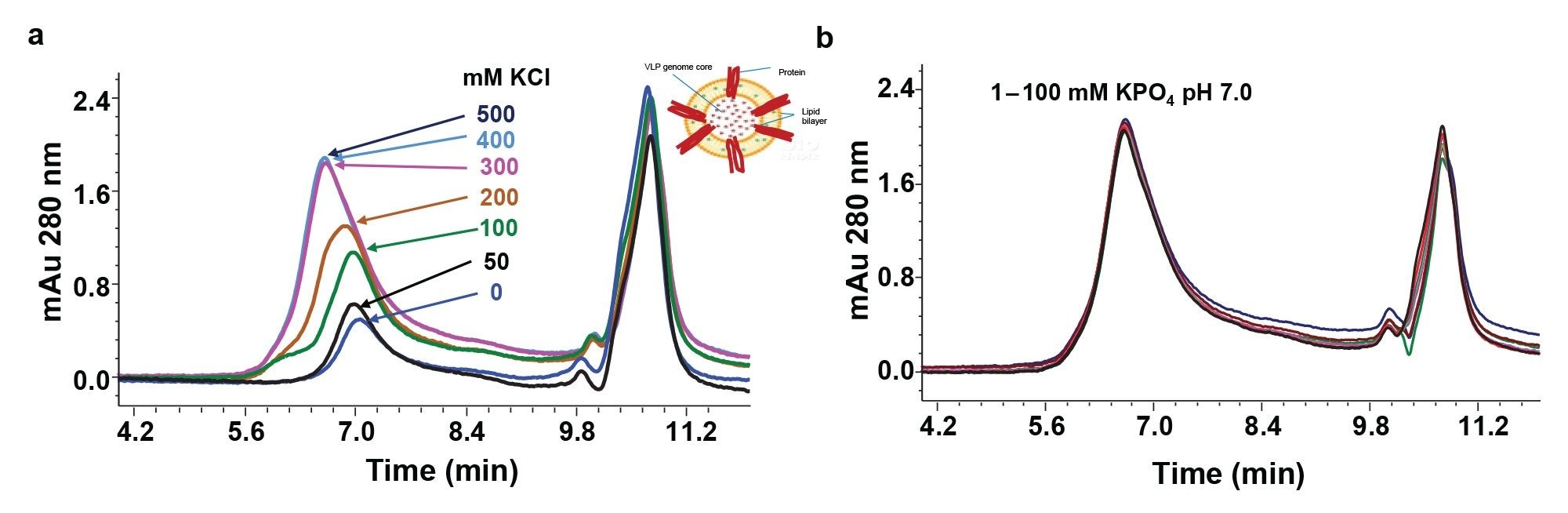

Characterization of any biotherapeutic by SEC requires identification of optimal mobile phase conditions to ensure a typical Gaussian peak shape is achieved for the analyte with minimal secondary interactions with column hardware or the packing material. It becomes even more challenging for complex modalities that contain multiple types of biomolecules, such as enveloped VLPs. Thus, a successful SEC analysis could require careful screening of mobile phase additives to maintain the integrity of membrane-bound viral capsids. Figure 2A illustrates the impact of ionic strength on the eVLP signal while performing SEC analyses.

The chromatographic peak height and area continuously improved with increasing potassium chloride (KCl) concentration - up to 400 mM. Further increase of ionic strength to 500 mM did not improve the UV signal, suggesting that 400 mM is the optimal ionic strength for analyzing this eVLP. Incidentally, changes in buffer strength (1-100 mM) had no impact on the UV signal intensity when the ionic strength was maintained at a constant level of 400 mM (Figure 2B). Furthermore, the change from KCl to NaCl did not affect the chromatographic profile (data not shown).

Our previous studies with lipid nanoparticles indicated better recovery when PS-80 was included in the mobile phase.8 This possibility was explored along with a sucrose additive to improve eVLP recovery. These studies revealed that PS-80 at 60 ppm and 125 mM sucrose improved recovery (data not shown). Furthermore, the modified buffer which consists of 2x DPBS with 0.006% PS80, and 25% sucrose (125 mM) appeared suitable for the evaluation of this eVLP formulation. The studied eVLP contained trehalose as a stabilizing agent. Although trehalose and sucrose are both disaccharides, their stabilizing effects may differ with the eVLP. However, the use of sucrose additive in the mobile phase was due to prior experience and to mimic trehalose closely.

Biophysical Characterization

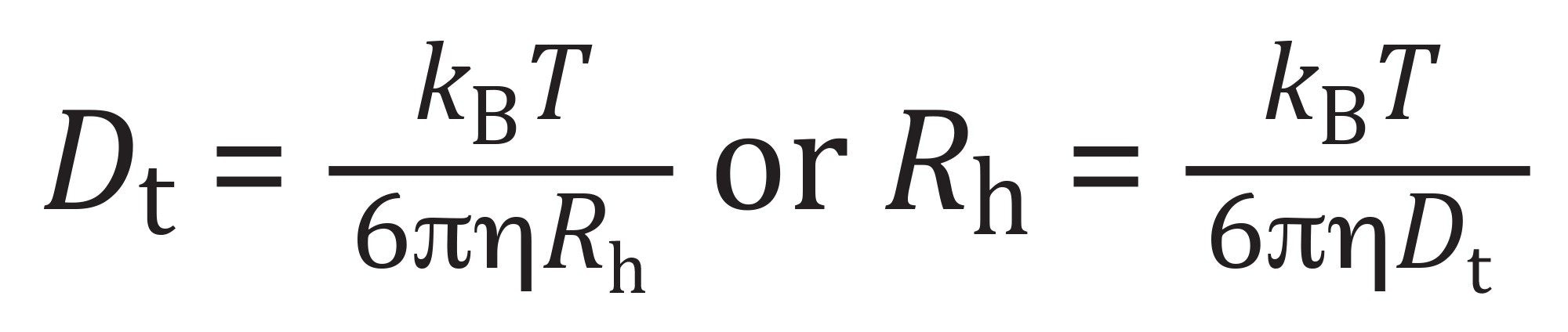

DLS is often used as a rapid, nondestructive measurement for VLPs to assess quality and impurities, such as aggregates.9–10 To get a preliminary view of the size distribution and polydispersity of the enveloped VLP, DLS analysis was performed using a DynaPro NanoStar Instrument. DLS measures the hydrodynamic radii of particles in a solution by monitoring the fluctuations in the intensity of the scattered light due to Brownian motion. In batch mode, all particles are measured simultaneously without physical separation. The time-dependent intensity fluctuations are processed through an autocorrelation function (ACF), from which the translational diffusion coefficient is determined. This coefficient is then used in the Stokes-Einstein equation (Equation 1) to determine the hydrodynamic radius of the particles:

where Dt = translational diffusion coefficient, kB = Boltzmann constant, T = absolute temperature (Kelvin), ɳ = viscosity of the solvent, and Rh = hydrodynamic radius of the particle.

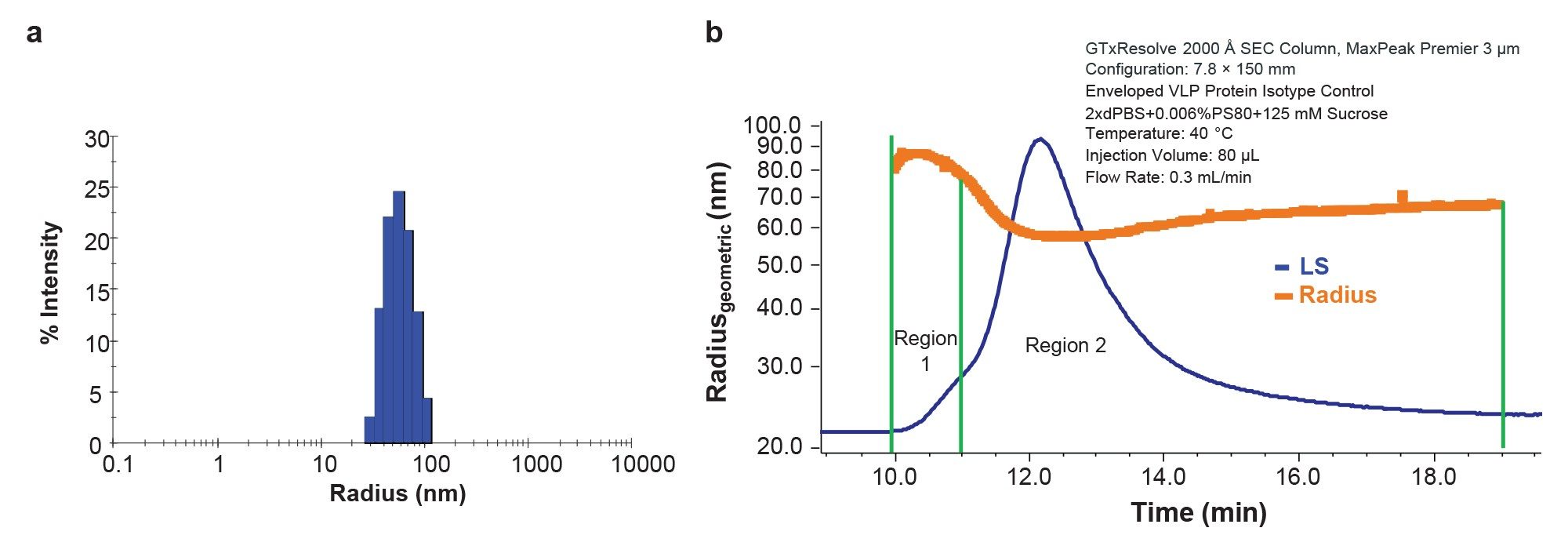

This analysis indicated an average particle hydrodynamic radius of 59.9 ± 0.2 nm (Figure 3A) and polydispersity (PDI) of 0.10 ± 0.04. No additional populations of very large aggregates or small fragments were observed. Simultaneous SLS measurements estimated the total concentration of VLP as 1.2×1011 VLP/mL. Although the lack of other species and low PDI suggests a relatively uniform population, DLS cannot resolve particles with similar sizes, such as singlets and doublets. The process of enveloping the VLP may also impart some degree of polydispersity, compared to a purely proteinaceous capsid, similar to lentiviral vectors and other enveloped viruses.11 Fractionation by SEC coupled with detailed biophysical characterization by MALS provides more thorough particle size distribution and detailed particle concentration analysis.

Separation by SEC or field-flow fractionation (FFF) coupled with MALS can provide absolute molar mass and size of the eluting molecules and particles, independent of conformation or elution time.12–13 In addition, for particles with a known shape, the total particle concentration can be directly measured by light scattering.14–15 This technique has been applied to a variety of virus structures, and total physical titer measured by light scattering can be considered as part of the quality control process for vaccine production.11–18 The increased resolution and detail provided by SEC or FFF coupled with MALS can provide key details into the distribution of particle sizes that would otherwise be missed by batch DLS.19

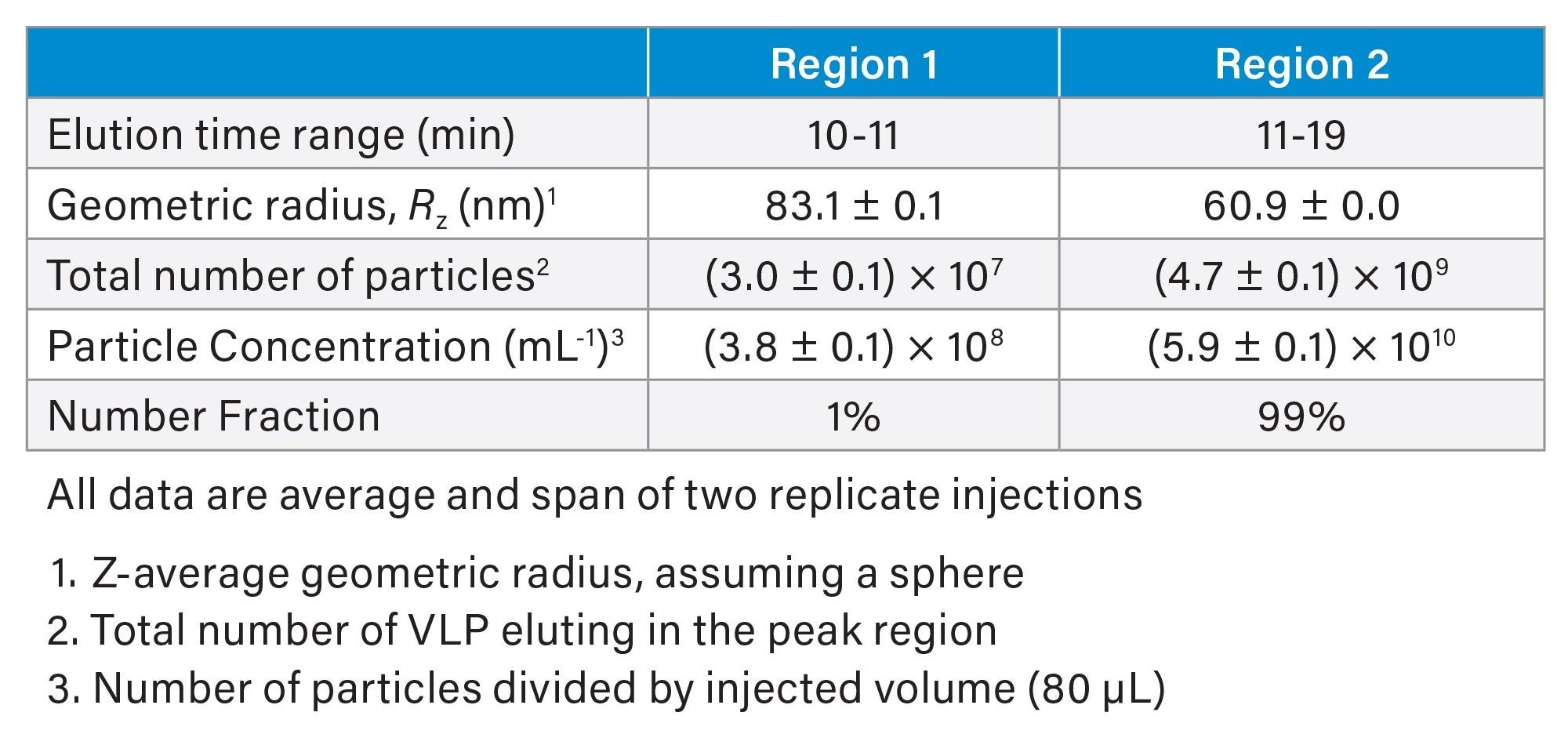

SEC-MALS analysis of the eVLP (Figure 3b) under the optimal conditions described above showed a distinct chromatographic profile with a shoulder at the leading edge (Region 1) containing larger particles and main peak (Region 2) containing mostly singlet VLPs. Online MALS analysis provided the geometric radius of the eVLPs, assuming a spherical shape. As shown in Figure 3b, the size is relatively constant across Region 2 with Rz = 60.9 nm (Table 1). This value is in excellent agreement with the hydrodynamic radius measured by batch DLS, suggesting the particles are indeed spherical and of relatively uniform size. Region 1 consists of a small fraction of larger particles, likely doublets and higher order species. The measured radius ranged from 78 nm to 88 nm, suggesting coelution of multiple species outside the resolving power of the column.

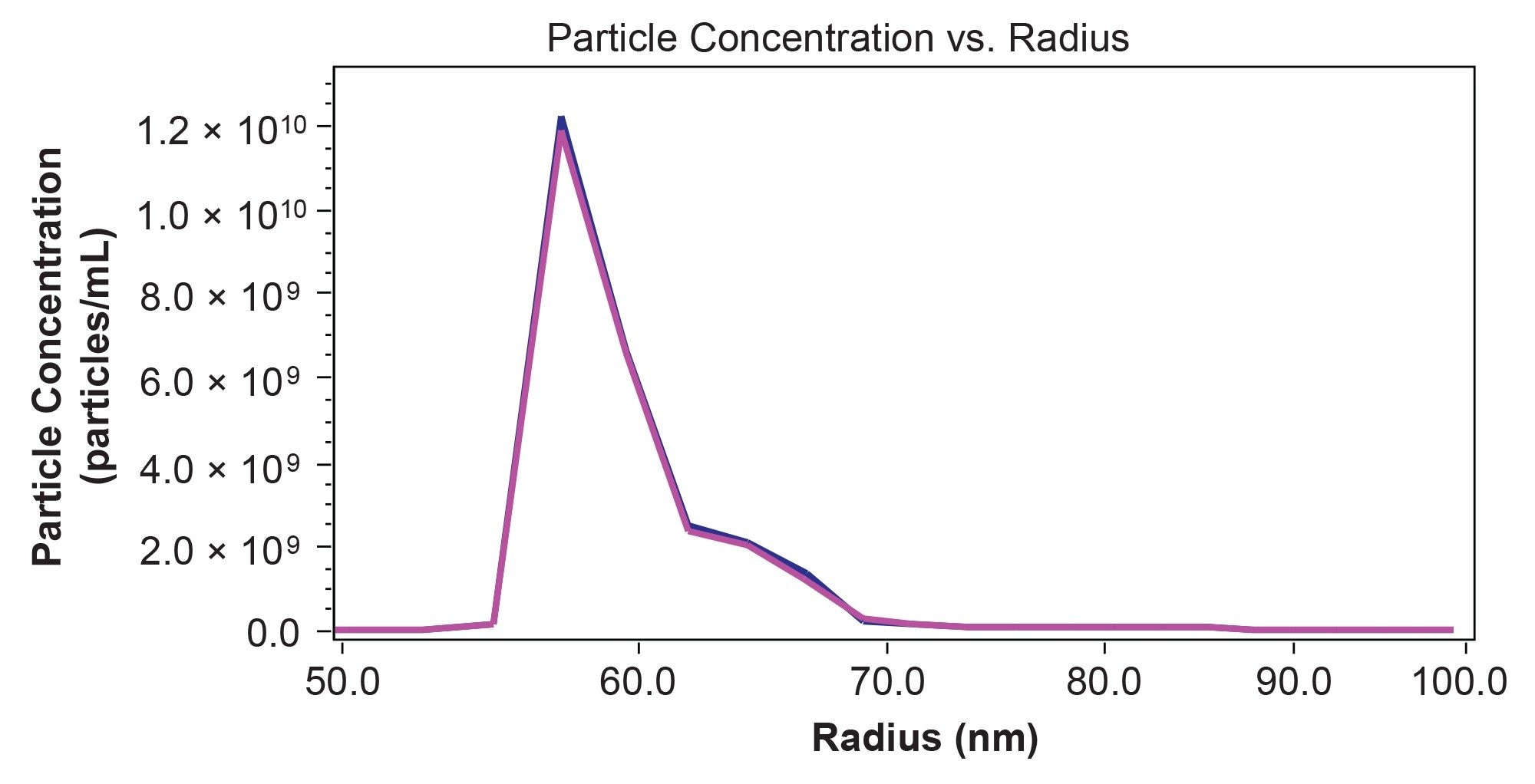

In addition to the average size across a peak region, MALS enables calculation of particle size distribution with greater detail compared to DLS. This type of information may be useful for understanding product performance or potential immunogenicity. The particle size distribution in Figure 4 clearly shows the two different size populations that were not resolvable by batch DLS along with quantitative information about the concentration of the different particle sizes. In this case, the concentration of particles with radius <62 nm is 4.9×1010 VLP/mL, representing 85% of the solution. Another 14% of the sample (8.3×109 VLP/mL) are between 62 nm and 70 nm in radius. Less than 2% of the eluting VLPs are >70 nm.

Finally, the size and particle concentration measured by MALS can provide key information for further method optimization. For example, some tailing is observed in all detectors (UV, MALS, and RI) that extends to the total inclusion volume of the column (Figure 3b). This is accompanied by significant measurable radius and even a slight increase. This behavior could be attributed to larger species being retained on the column due to anchoring or non-specific interaction.12 Moreover, the total particle concentration measured by SEC-MALS is ~50% of the total concentration in batch by simultaneous static and dynamic light scattering. This level of recovery appears to be reproducible since the peak areas and retention times remain constant across multiple injections. Some mismatch between the techniques is expected since batch DLS cannot resolve and count singlets separately from the larger aggregates, and separation combined with quantification by MALS will provide a more accurate particle concentration. However, the apparent decrease in particle concentration could also suggest retention of a specific population on the column or other sample degradation. Separation and quantification by FFF-MALS, where the separation is performed without a stationary phase, could provide orthogonal data to understand this behavior and ensure that the SEC-MALS method is fit for purpose.

Conclusion

The results in this application note demonstrate that the GTxResolve 2000 Å SEC Column, MaxPeak Premier 3 µm, offers the appropriate pore size and column technology to facilitate the biophysical characterization of an enveloped VLP. The use of SEC-MALS served as an orthogonal technique to batch DLS, highlighting additional biophysical characteristics of this eVLP sample. The optimized method and mobile phase produced enhanced eVLP recovery and facilitated partial resolution of the monomer from aggregate components. Overall, this combination of GTxResolve SEC Column technology plus MALS with online QELS provides a platform technique for characterizing biomolecular complexes, such as an eVLP.

References

- He, J. et al. Virus-like Particles as Nanocarriers for Intracellular Delivery of Biomolecules and Compounds. Viruses 14, 1905 (2022).

- Tariq, H., Batool, S., Asif, S., Ali, M. & Abbasi, B. H. Virus-Like Particles: Revolutionary Platforms for Developing Vaccines Against Emerging Infectious Diseases. Front. Microbiol. 12, (2022).

- Zhang, L. et al. Virus-like Particles as Antiviral Vaccine: Mechanism, Design, and Application. Biotechnol Bioprocess Eng 28, 1–16 (2023).

- 4. Wetzel, D. et al. Bioprocess Optimization for Purification of Chimeric VLP Displaying BVDV E2 Antigens Produced in Yeast Hansenula polymorpha. Journal of Biotechnology 306, 203–212 (2019).

- Redecker, A. S., Neek, M., Smith, P. E. J. & Swartz, J. R. Multifunctional Nanoparticle Platform for Targeted Delivery and Vaccines. iScience 28, (2025).

- Camacho, K. J. et al. Bridged Ethylene Polyethylene Oxide Surfaces to Improve Packing Materials for Widepore Size Exclusion Chromatography. Journal of Separation Science 47, e202400541 (2024).

- Kulyabina, E. V., Kulyabina, T. V., Grebennikova, T. V., Morozova, V. V. & Morozov, V. Yu. Virus-Like Particles: Properties and Characteristics of Reference Materials. in Reference Materials in Measurement and Technology (eds. Sobina, E. P. et al.) 23–30 (Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham, 2024). doi:10.1007/978-3-031-49200-6_2.

- Finny, A. S. et al. Efficient Profiling of Lipid Nanoparticle Formulations Using Waters GTxResolve 2000 Å SEC Column, MaxPeak Premier 3 µm. Waters Application Notes. 720008797. 2025.

- Some, D. WP9003: VLP Characterization with the Light Scattering Toolbox. https://www.wyatt.com/library/application-notes/wp9003-vlp-characterization-with-the-light-scattering-toolbox.html (2019).

- Challener, C. A. Dynamic Light Scattering for Non-Destructive, Rapid Analysis of Virus-Like Particles. BioPharm International 28, 46–49 (2025).

- Sripada, S. A. et al. Multiangle Light Scattering as a Lentivirus Purification Process Analytical Technology. Anal. Chem. 96, 9593–9600 (2024).

- Striegel, A. M., Brewer, A. K. & Zielke, C. Size-Exclusion Chromatography with Multi-Angle Static Light Scattering. Nat Rev Methods Primers 5, 40 (2025).

- Wyatt, P. J. Light Scattering and the Absolute Characterization of Macromolecules. Analytica Chimica Acta 272, 1–40 (1993).

- Wyatt, P. J. & Weida, M. J. Method and Apparatus for Determining Absolute Number Densities of Particles in Suspension. 13 (2004).

- Wyatt, P. J. Measurement of Special Nanoparticle Structures by Light Scattering. Anal. Chem. 86, 7171–7183 (2014).

- Bousse, T. et al. Quantitation of Influenza Virus using Field Flow Fractionation and Multi-Angle Light Scattering for Quantifying Influenza A Particles. Journal of Virological Methods 193, 589–596 (2013).

- Wei, Z. et al. Biophysical Characterization of Influenza Virus Subpopulations Using Field Flow Fractionation and Multiangle Light Scattering: Correlation of Particle Counts, Size Distribution and Infectivity. Journal of Virological Methods 144, 122–132 (2007).

- Deng, J. Z. et al. SEC Coupled with In-Line Multiple Detectors for the Characterization of an Oncolytic Coxsackievirus. Molecular Therapy - Oncolytics 24, 139–147 (2022).

- Padilla, M. S. et al. Elucidating Lipid Nanoparticle Properties and Structure Through Biophysical Analyses. Nat Biotechnol 1–14 (2025) doi:10.1038/s41587-025-02855-x.

720009166, November 2025